When did magic die for you?

I always believed in magic.

I mean, really believed in it.

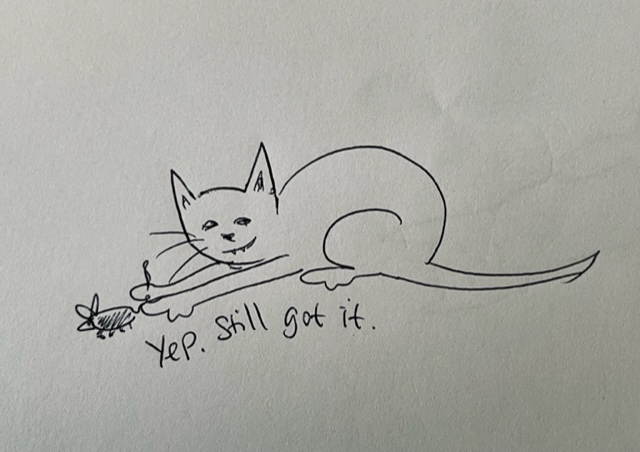

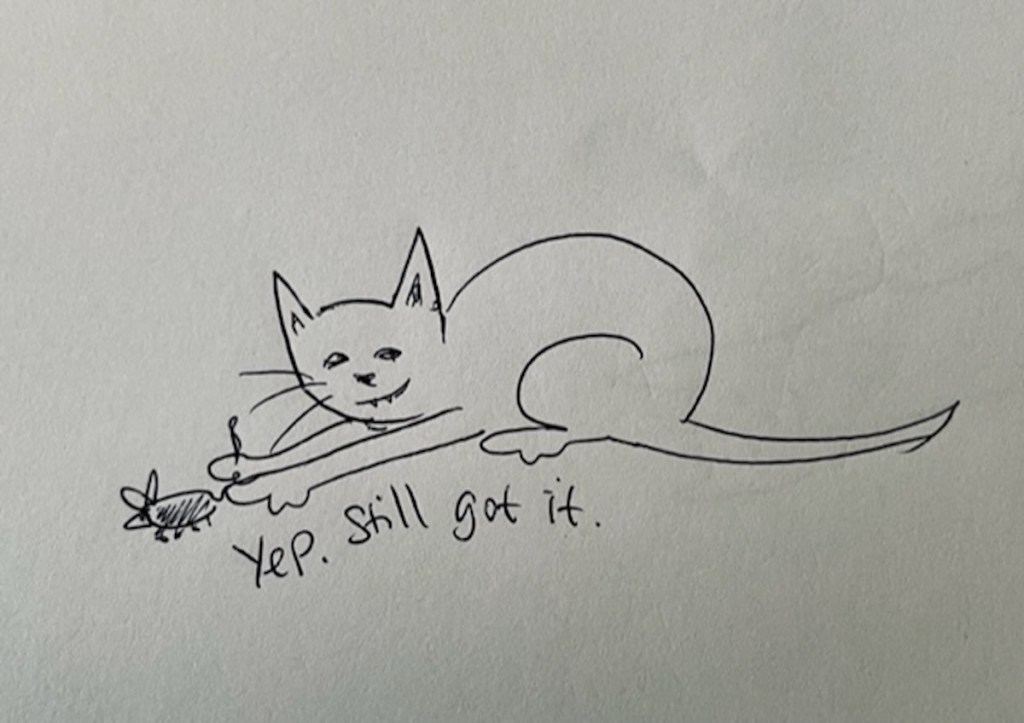

Aged 9 I thought if I wished hard enough my cat would talk to me. That he was only hiding his secret self behind his impassive cat face because he could not trust a human. Could never trust a human, not even me. Because the truth was cats were sentient beings, velvet fur-clad Princes in disguise.

“You can trust me”, I urged into his flickering ear.

I whispered. I pleaded with him.

I begged and worshipped, adoring at his side.

But he just smiled that secret cat smile. He stretched and purred, and he said nothing.

I thought that he was hiding his magic from me because I didn’t believe strongly enough.

In my bookish world talking cats, magic carpets and enchanted woods were possible, even probable.

I was a dreamy, highly imaginative child. A bit frail, frequently off school ill with throat-closing tonsillitis or conjunctivitis. I was no good at sports, and had a lazy eye corrected by operations and interventions that still left me as a wearer of glasses.

Much of my time was spent reading and re-reading books I had at home (not enough books I am sad to say – my family were not book-ish people).

Watership Down was read to rags. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The Puffin Book of Jokes. Herbert Van Thal’s Horror Anthologies. The Sun newspaper … yeh, I know 😦 Everything and anything that was left lying around I would read. Looking back, there were definitely some books around at home that an impressionable child shouldn’t read. But that’s another story for another time.

I believed that magic was out there, waiting for me, and if I just thought about it hard enough, I could break through to the real enchanted world.

I saw everything as a possible gateway to a magical realm. A vast old oak tree – where was the small hidden doorway to Elf Land? An ancient flagstone wall – which stone did I need to tap upon thrice to open the secret portal? An empty room in an abandoned house, an overgrown garden – what magic might be there, hiding from me?

If I could only murmur the right combination of words, make the right gestures, I would be invited to step through into the Real World. The magical world, where I properly belonged.

I picked flowers and leaves in the fields and woods, chanting made-up songs. I wore my jumper inside out and turned it back again, in the vain hope that the fairy folk would come and claim me, and take me home with them. (Grandma had warned me the fairies would steal me if I did this, but it sounded like a brilliant opportunity to me.)

I wanted to be away from this banal, bland place of grey rainy streets, bus tickets, supermarkets and school timetables.

I so obviously did not belong here.

Surely I had enough belief for them to accept me, and let me in?

Aged 11 I laid on the shingle of a beach and called to the mermaids to show themselves to me.

At that time I had read no T.S. Eliot or J. Alfred Prufrock. I just wanted the fantasy to be true so very, very much. I thought I might hear the mermaids singing. I thought I might see a silver tail splash above the waves.

If the mermaids had called me, I would’ve gone.

I was in search of magic everywhere. I would often wander away on family trips or holidays to find a deserted stretch of beach, a quiet woodland glade or empty river’s edge in the hope that the fairies might find me and come for me.

I would wade deep into caves on Cornish beaches, hoping I might be the one to find the last dragon in the world, sleeping inside on a pile of dim treasure.

I would dawdle behind on visits to old castles or ancient stone circles in the hope that something would recognise me, reach out to me. Speak to me.

I would leave out useful things like cotton reels and pins and sweets to help The Borrowers, who must surely live behind our skirting boards.

I just wanted to see that there was something else besides the plainness of this ‘life’.

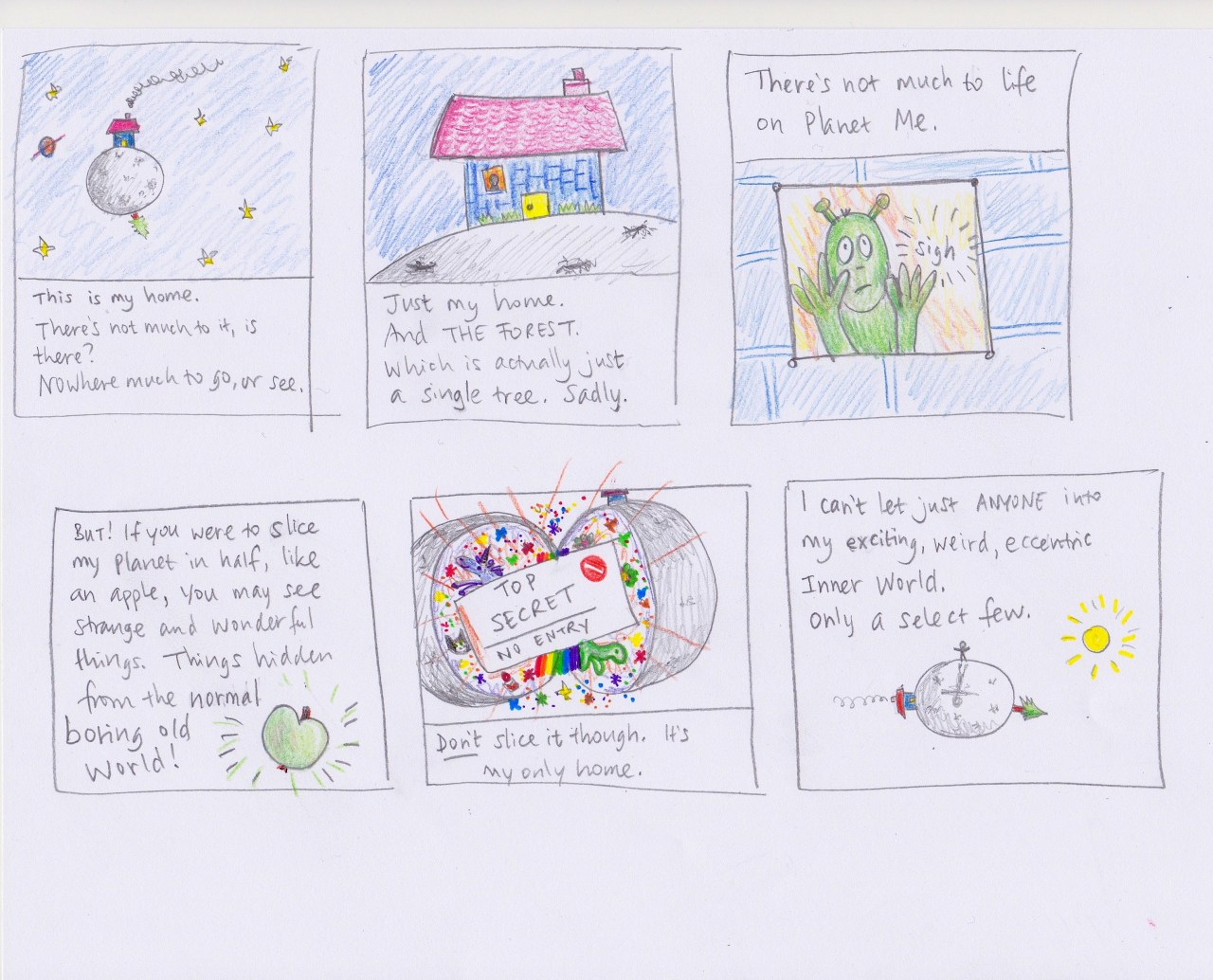

At one point I thought I must be an alien. That my Earth mum and dad had adopted me, but never told me the truth about how I had come to them.

My real mother was a beautiful, exotic alien being who had left me to brought up on earth (for some never explained reason).

Oh how I wished my Alien Mum would come and get me. To take me back home to my real planet again.

Maybe this was all part of a dissociation I’ve had since childhood, where I couldn’t believe I was really alive. I had died on the operating table aged three, when I was in hospital for my bad eye. Everything I was experiencing was a dream. I was in a coma. My real life would start when I woke up.

Then later, I was just in a film. It was all scripted. Phones would ring on cue. People would say things. Bad stuff happened. Good stuff happened. I wandered through it all, thinking it was all controlled by some mystic level film-makers.

This couldn’t be the real life. Because there was no magic being written into my script.

But it had to exist. It had to.

Father Christmas was one of my proofs that magic had somehow survived in this harsh and boring world. These days, I am embarrassed to admit that at an age when other girls were talking about their first French kiss, buying lipstick or getting their periods, I still believed in Father Christmas.

The magical man-god in the red and white fur coat who would fly across the world in one night – one night! – to deliver brightly wrapped presents to all the good children.

I knew He was real.

On Christmas Eve night you could strain your ears and hear the distant shiver of silvery bells as the reindeer flew overhead. You could hear the gentle thump of hooves landing on the roof above you. You’d scrunch your eyes, up, tight. Because if you weren’t asleep, he wouldn’t come.

That’s a part of magic. You have to be in an altered state of consciousness for it to happen.

Then in the greyness of early Christmas morning, you’d open your tired, gritty eyes and stretch your toes down the bed and … YES! The exciting crackling sound of wrapped boxes that told you He’s Been.

The Magic had happened once more.

How delicious and wonderful it would be to go back for one night to experience that wonder filled, fairy-lit feeling.

It was my First Year at senior school when Father Christmas died.

I was sitting at a battered old desk, dragging my brain through a dull Double Maths class. The horridly constricting light blue squares of my maths exercise book were in front of me, squashing me in.

(I hate graph paper, lined paper, or anything that squeezes thinking into a tight box or a linear pattern. The horrible horror of imprisoning your bright zippy brain into someone else’s pre-printed pattern. Ugh. They should be banned, along with Xcel sheets.)

It was autumn, my first term at Big School (which I already hated so much it gave me stomach ache). As I scrawled meaningless numerals into the overbearing squares to complete some irrelevant skill like long division, I had a sudden realisation.

There was no magic in this world.

How could magic exist in a dull world of long division, bored teachers, brutal PE lessons and computers?

And if there was no magic, there was no Father Christmas.

Of course there wasn’t a Father Christmas. A magical man-spirit delivering gifts to children all over the world?! What kind of planet did I think I was living on?

I looked up from the mind-strangling squares. The more I explored the thought of no Father Christmas, the more mind-shocked I felt.

I happened to be sitting near a window on the second floor of the school block, and could see a busy traffic light intersection from the stuffy classroom.

The lights turned red. The boring cars stopped. The lights turned green. The boring traffic moved off.

It was all so obvious. How could I have been so stupid? So blind? So utterly THICK?

Magic wasn’t here. It never had been here. I’d never even been close.

I remember trying not to show the enormous tragedy of it on my face in that dull lesson in that dusty classroom.

The sudden and complete realisation that magic, true magical magic, did not exist for me, or for anyone.

The sadness was real and immense.

I had to swallow a lump in my throat and my eyes bubbled, threatening to overflow with tears.

It was the December before my twelfth birthday, and the depression of my realisation overwhelmed me.

Christmas was not magic any more. All the gifts were cheap perfume, bad socks and pointless soap-on-a-rope.

When we went to the beach the next summer I didn’t bother speaking to the waves again.

When we walked in the woods I didn’t stop to talk to the trees.

I realised Father Christmas was my Earth Mum.

And I was all alone with my misery, because no-one else felt like me, or was as stupid as me about belief in magic.

Perhaps you can tell me different. Perhaps you believed in these things too?

Now I am old, I still want to believe in magic.

I do sometimes go and talk to the trees, and whisper to the sea, when I have a chance. But I know they won’t respond. I think I am too old now.

I do still think about that spaceship landing and finally taking me back Home. The woken dragon flying me away to the beautiful realm where my people welcome me. The fairies taking pity on me (at last!) and leading me to the shimmering glades where I belong.

Until then, I wait for my true life to begin.

Magical worlds …

Clive Barker’s Weave World is the closest thing I’ve read to putting across what I mean. It makes the idea that you could suddenly enter a magical realm, away from this mundane reality, quite believable.